The global security environment is undergoing rapid transformation, shaped by geopolitical tensions, technological disruption, hybrid threats, and converging cyber-physical risks. For industry leaders, these shifts have direct implications for supply chain resilience, critical infrastructure protection, and competitive advantage. Navigating this landscape demands proactive risk intelligence, investment in security innovation, deep public–private collaboration, and industrial capacity building. Security leaders will require strategic foresight, operational preparedness, and directional approaches to safeguard business interests in an era of persistent uncertainty and evolving threats.

We are amidst a world in flux. The post-Cold War peace dividend has been long exhausted. Great power rivalry is no longer theory, it is now a hard reality shaping policy planning across continents. The immediate period succeeding the end of the cold war defined by a unipolar world has now morphed into multi polar spheres of influence, aided in no small measure by the pivot to protectionism by the US, and has witnessed the start of a new cold war. A China which was biding its time for over two decades has now grown into its full potential. And to quote Graham Allison, the table is set for the Thucydides trap.

The rise of strategic multipolarity has been defined by the following contours:

The rise of strategic multipolarity has been defined by the following contours:

- China’s assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific.

- Russia’s disruptive revisionism in Europe and the Middle East.

- The West’s recalibration post-Afghanistan, Ukraine, the migrant crisis and economic

disruptions.

- The growing role of middle powers like India in shaping the balance.

Familiar global Institutions are under stress, with the UN becoming ineffective and the WTO and the IMF facing credibility challenges. The emergence of parallel frameworks like the BRICS, the SCO, I2U2, the Quad, and the AUKUS, highlight the evolving shift to groupings where there is a broad convergence of National interests. The erstwhile push towards globalisation, central manufacturing and outsourced supply chains has now given way to retrenchment, disruption in traditional alliances, nationalism and inward looking policies. The familiar rules based order is fast changing and to quote the aforementioned Thucydides, “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”.

Closer home India has two live disputed borders across which we have had conflicts with both adversaries in the past five years. Now, with the stated Indian government policy of treating any act of sponsored terror as an act of war and no separation between the actor who perpetrates terror and the agency that sponsors it, the region remains volatile. Further, technology has reduced the threshold of conflict and in effect, globally and regionally, we can conclude with some certainty that the risk of conflicts in the near and mid term, is high.

There are some clear conclusions that can be drawn from recent and ongoing conflicts worldwide, with implications for industry:

- Conventional state vs state conflicts are back as a tool of National policy.

- Alliances and partnerships matter when you are facing a stronger or a near peer adversary.

- Technology is the new oil. Having indigenous high end technology and the industrial capacity to scale production is a strategic advantage.

- A strong, competent and technologically current military is essential in the deterrence calculus.

- Economic capability and economic growth directly impact a Nation’s ability to grow military capacities, and a strong military provides you the confidence and stability to grow economically. One is not possible without the other.

From a national security standpoint, safeguarding the nation is no longer solely the military’s domain, as defence preparedness is now inseparable from industrial capability. In the information age, disruptions in semiconductors, rare earths, transistors, and similar critical components have emerged as strategic threats. Viewed through a material lens, industry forms the second frontline—driven by public–private synergy in defence R&D, national manufacturing strength as the determinant of war endurance, and the integration of dual-use technologies with civilian–military fusion as the foundation of military capacity.

While industry has become indispensable to national security, its vulnerabilities have grown in equal measure. Advancements in technology have heightened the susceptibility of critical infrastructure and economic security. The protection of energy grids, ports, and telecommunications networks is now imperative. In the future, industry and infrastructure operators may find it necessary to deploy private counter-UAS capabilities, much as they already provide physical security for their facilities and installations. Equally, cyber-resilient architecture across both military and civilian sectors is now a sine qua non for security preparedness.

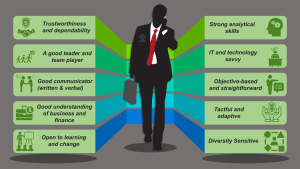

What is apparent today is that industry security is no longer a support function, it is now strategic, impacting brand reputation, investor confidence, compliance, and business continuity. The question is not if organisations will change with a changing environment but how will their leaders navigate that change. Security experts and leaders are now tasked with the unenviable job of predicting the future and positioning their organisations, facilities and teams to deal with supply chain disruptions, workplace stress and uncertainty, economic turbulence, cybersecurity and hybrid threats. However, in this environment of uncertainty, there are some things that continue to remain constant.

What is apparent today is that industry security is no longer a support function, it is now strategic, impacting brand reputation, investor confidence, compliance, and business continuity. The question is not if organisations will change with a changing environment but how will their leaders navigate that change. Security experts and leaders are now tasked with the unenviable job of predicting the future and positioning their organisations, facilities and teams to deal with supply chain disruptions, workplace stress and uncertainty, economic turbulence, cybersecurity and hybrid threats. However, in this environment of uncertainty, there are some things that continue to remain constant.

As professionals dealing with rapid change, there are certain skills that will remain relevant for security leaders. First and foremost is decision making. Most leaders who are not trained for the role tend to make decisions intuitively. However, in periods of change and transition, the need is to develop an aptitude and a comfort level in data driven decision making. It means identifying what specific data to get, collecting and recording that data as a consistent routine function and interpreting it objectively using tools.

Next, there is a need to be driven by a sense of urgency in what we do. In today’s world, rapidly-advancing technology and ever-shortening innovation cycles have limited space for deliberate seasoned processes. Therefore, the skill is in executing with 60-70% of the available inputs. In addition, a sense of urgency overcomes the inevitable inertia generated by repetitive analysis while also serving to encourage and motivate a team when backed by speedy and successful execution. For this, leaders have to be courageous enough to take thoughtful risks.

Next, there is a need to be driven by a sense of urgency in what we do. In today’s world, rapidly-advancing technology and ever-shortening innovation cycles have limited space for deliberate seasoned processes. Therefore, the skill is in executing with 60-70% of the available inputs. In addition, a sense of urgency overcomes the inevitable inertia generated by repetitive analysis while also serving to encourage and motivate a team when backed by speedy and successful execution. For this, leaders have to be courageous enough to take thoughtful risks.

Leaders have to transition from certainty to curiosity. In dynamic environments, confidence without curiosity is a liability. In such a climate, strategic listening is a leadership act. As we become used to easy answers, we are forgetting how to ask questions. Curiosity is the wellspring of strategies for identifying and solving problems effectively. An identification strategy that unpeels layers of situational data is based on asking the right questions.

Leaders need to shift emphasis from efficiency to resilience. The erstwhile focus on,“run lean, reduce risk, cut redundancy” needs to give way to “building shock absorbers, strengthening systems, supporting wellbeing.” In times of disruption, it’s not the most efficient organisations that survive, it’s the most adaptable. Leadership must prioritise resilience of systems and people. This includes robust incident response, backup plans, stress-tested SOPs and also ensuring teams are not burnt out or disengaged.

Leaders need to shift emphasis from efficiency to resilience. The erstwhile focus on,“run lean, reduce risk, cut redundancy” needs to give way to “building shock absorbers, strengthening systems, supporting wellbeing.” In times of disruption, it’s not the most efficient organisations that survive, it’s the most adaptable. Leadership must prioritise resilience of systems and people. This includes robust incident response, backup plans, stress-tested SOPs and also ensuring teams are not burnt out or disengaged.

A leadership style that highlights decentralisation and delegation is an inescapable requirement of the 21st century, where the need is for multidisciplinary teams with an end-to-end vision. These teams require autonomy to function effectively. Does this mean that a leader, will have to give up some command and control? Unambiguously, yes. The principle of trust but verify is well known, and can very well be adapted to delegate but monitor. Delegation is also important considering the span of effective control of a leader and the need to give a sense of agency to team members.

For people to respond, they need to have trust and faith in the leader, that gives them the assurance and confidence that seemingly adverse decisions have organisational good underpinning it. Towards this, communicating extensively and seeking credible feedback forms the backbone of evoking a feeling of trust and faith. This would appear self evident, however, the number of cases where a lack of communication and reluctance to take feedback have derailed projects and organisations, indicate the difficulty in ensuring this as a functional culture.

Leadership needs to be fully involved in the nuts and bolts of the operation to be ahead of the curve, otherwise decisions and executive actions that fall within the remit of the leader will be hostage to the timelines of the person who has his hands dirty. This does not imply that leaders should micro manage, what it means is, leaders should be fully conversant with the details of their operation. Once they have this familiarity, an effective leader monitors the pulse points in a way that anything untoward or unplanned is identified without delay. This is especially essential if a leader is driving change. Having expertise in the nuts and bolts of the operation has to be balanced with widening the field of vision and enlarging leadership worldview. Leaders function at the extremes of the awareness spectrum.

Finally, there has been a lot of talk on Work-Life balance. However, in the words of John Carmack, a legendary programmer and engineer best known for co-creating groundbreaking video games like Doom and Quake and pioneering 3D graphics technology, while working smarter not harder is fine, but there’s a quality to obsession that’s really hard to match any other way. Sometimes important insights come only from a total immersion in a problem or field. And even when the work is mundane, there’s value that you can extract from that.

Finally, there has been a lot of talk on Work-Life balance. However, in the words of John Carmack, a legendary programmer and engineer best known for co-creating groundbreaking video games like Doom and Quake and pioneering 3D graphics technology, while working smarter not harder is fine, but there’s a quality to obsession that’s really hard to match any other way. Sometimes important insights come only from a total immersion in a problem or field. And even when the work is mundane, there’s value that you can extract from that.

Consistent organisational routines manifest in organisation culture. And organisation culture decides the long term success of any company or organisation. One of the key challenges for any organisation is developing and maintaining the right company culture. The best organisations understand the importance of routines and the worst ones are headed by people who never thought about it and wondered why no one followed directions.

Organisational culture flows from the top. To build a healthy culture, leaders must be proactive and intentional—otherwise, a culture will form on its own, like weeds, and it will likely be one they are unhappy with.

In the Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change 1982, Richard R. Nelson and Sidney G. Winter focus their critique on the basic question of how firms and industries change over time. In nearly 10 years of examining mass of data, the central conclusion of the book was “Much of a company’s behaviour is best understood as a reflection of general habits and strategic orientations coming from the company’s past”. Not rational choices made through deliberate decision making.

Organisationally, in today’s fast-moving world, companies must navigate two constant operational realities: change and uncertainty. In the security industry, the shifts we are witnessing are not mere incremental adjustments but large-scale transformations. We are moving from traditional physical security to AI-enhanced systems, from isolated threats to converged cyber-physical risks, and from rigid, linear hierarchies to agile, cross-functional teams.

While leaders face difficult challenges, one thing is proven, the more complex and elusive the problems are, the more effective problem solving through trial and error becomes in comparison to the alternatives. The adaptive experimental approach can work almost anywhere.

While leaders face difficult challenges, one thing is proven, the more complex and elusive the problems are, the more effective problem solving through trial and error becomes in comparison to the alternatives. The adaptive experimental approach can work almost anywhere.

In conclusion, geopolitics in the 21st century will not be defined by a single superpower but by the interplay of many. India’s rise will depend not only on the might of its armed forces but on the depth of its strategic industries, the agility of its institutions, and the unity of its people. Security professionals are trained to anticipate the worst, but as leaders, they must also inspire the best—in people, in systems, and in themselves. Change is not the enemy. Poor leadership is. In this age of complexity, clarity, courage, and consistency are the real force multipliers. Leaders should lead with intent, with integrity, and always keep in mind that their leadership shapes not just policy, but possibility.

The author, after superannuating from the Indian Army, now serves as a strategic advisor to leading organisations, drawing on his extensive experience in risk assessment, defence technology, organisational transformation, leadership, and motivation. This article is an abridged version of his talk delivered at the ASIS South Asia Meet on 26 July 2025 in Bengaluru.