Terrorists choose their moments with precision; nations fall only when they fail to read the message hidden in those moments.

The blast in Delhi at 7 pm on 10 November 2025 arrived without warning, tearing through the rhythm of an ordinary day, killing at least 8-13 and injuring 20-30 people, and reminding the nation once again that its capital is always a living target in the crosshairs of those who wish to destabilise India.

What we know so far, pieced together from television coverage and a series of selective police leaks, is troubling but still far from complete. An improvised explosive device was placed inside a moving Hyundai i20 driven by Dr Umar Un Nabi, an assistant Professor at Al Falah University, Faridabad in Haryana.

The car exploded near a traffic signal in the densely packed Delhi’s Red Fort area, timed with deliberate precision for maximum psychological shock. Initial forensic assessments shared off-record suggest the device had been assembled with a degree of expertise uncommon in amateur operations.

The car exploded near a traffic signal in the densely packed Delhi’s Red Fort area, timed with deliberate precision for maximum psychological shock. Initial forensic assessments shared off-record suggest the device had been assembled with a degree of expertise uncommon in amateur operations.

Some officers have hinted that DNA traces recovered from the vehicle may belong to Dr Nabi, who has been missing for several days, an unsettling possibility that ties into the larger pattern of professional radicalisation we have been witnessing in recent years. Yet none of this is definitive, and much of it is being revealed in fragments, shaping public expectations without providing clarity.

What remains unknown is far more consequential. We still do not know whether this was the work of a lone radicalised individual, a fledgling urban module, or a node connected to a wider terror architecture operating out of the Valley or across the border.

Investigators are probing encrypted communication channels and financial trails, but no single narrative has yet emerged. There are whispers about cross-border handlers, suggestions of a sleeper module being activated after a long dormancy, and speculation that the blast may have been a test run to assess Delhi’s response grid.

We do not yet know whether this was a standalone strike, a symbolic message, or the first tremor of a larger campaign waiting to unfold. And it is within this uncertain space, between what the police are selectively confirming, what they are deliberately withholding, and what still lies completely obscured, that the real danger resides.

These first images of the Delhi blast pulled me back into a world I thought I had left behind when I hung up my uniform, almost eight years ago. Even after years of retirement, the instinct to assess, to connect dots, to question the unseen motives behind an explosion comes back with a force that feels almost physical.

You never really stop being a soldier in this line of work; you simply move further away from the noise, as I did when I moved away to settle in Pune, and yet the noise followed me. As I watched the smoke rising in the nation’s capital on my television screen, I realised again that these shocks do not merely wound the city; they bring back decades of memories for those of us who have operated in the shadows of similar crises.

This latest incident in Delhi is not just another attack. It is part of a continuing arc of threats that have evolved, multiplied, and adapted since the first organised terrorist strikes on Indian soil.

“I have stood at blast sites as a young officer and as an old one. The smell of explosives never changes, but the lessons we fail to learn always return.”

“I have stood at blast sites as a young officer and as an old one. The smell of explosives never changes, but the lessons we fail to learn always return.”

When I joined the Army in the late seventies, terrorism against India was still a regional phenomenon; Punjab would soon erupt, Bengal was dealing with Naxalism, and the Northeast fire, which started in 1956, was still very much raging. But it was in the nineties that we saw the shape of a new enemy emerging. It was no longer about insurgency; it was about terrorism backed by a hostile state, Pakistan, trained in its camps, guided by its intelligence services, and inserted into our cities with clear strategic aims.

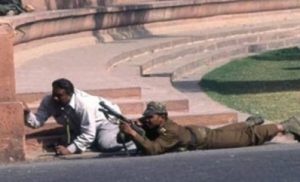

The 1991 Lajpat Nagar attack, the 1993 Delhi bomb blasts, and the serial train bombings of the same year showed us that Delhi was not beyond reach. But it was the 2001 Parliament Attack that changed everything. I remember that day vividly. Many of us in uniform knew instantly that this was not an improvised plan; it carried the trademark of Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, groups that were trained, funded, and directed by Pakistan’s state machinery. The audacity of attacking the heart of Indian democracy was meant to send a signal: the enemy could strike at will.

In counterterrorism, nothing is random. Not the blast, not the timing, not the silence before it.”

In counterterrorism, nothing is random. Not the blast, not the timing, not the silence before it.”

After 2001, Delhi became a focal point of their terror architecture. The 2005 Diwali-eve blasts that tore through Sarojini Nagar, Paharganj, and Govindpuri reminded us that terrorists understood how to exploit crowds and festivities. In 2008, when serial blasts rocked Delhi again, we saw a shift.

Indian Mujahideen had begun to emerge as a decentralised, ideologically driven network of radicalised youth operating within Indian cities, guided by handlers abroad but functioning semi-independently. That was a warning sign. It showed us that terrorism had seeped into the urban fabric, exploiting social fractures, anonymity, and the immense complexity of a megacity.

This new blast in Delhi fits into that lineage, but with a contemporary twist. The timing suggests deliberation. The choice of location suggests a probing action, something designed to test the response grid, not provoke a massive counterstrike. And the nature of the device indicates a level of access and planning that small, self-radicalised cells often possess today. I have noticed over the years that terrorists rarely strike for spectacle alone. They strike when they want to pressure the political system, when they need to reassert relevance, or when their external handlers want to shift public attention. This attack feels like part of that larger psychological game.

“If you trace the blasts from Lajpat Nagar to Parliament, from Sarojini Nagar to Pulwama, the pattern is unmistakable: the enemy adapts because we allow ourselves the luxury of forgetting.

”What most civilians do not realise is that terrorism, especially the kind we face, is never just about ideology. It is about strategy. Every bomb, every blast, every unexpected violent act is a message from the network that sponsors and sustains it. And those networks have a long history.

”What most civilians do not realise is that terrorism, especially the kind we face, is never just about ideology. It is about strategy. Every bomb, every blast, every unexpected violent act is a message from the network that sponsors and sustains it. And those networks have a long history.

Pakistan’s ISI has not changed its doctrine of proxy warfare in forty years. What changed instead was the nature of the proxies. After the United States’ pressure post-9/11, Pakistan did not dismantle its terror infrastructure; it diversified it. Lashkar and Jaish remained the core, but numerous splinter groups, front organisations, ideological charities, and hybrid radical collectives began to grow.

Pathankot in 2016 showed us how Pakistan continued to use infiltration from across the IB. Uri later that year showed the same intent. Pulwama in 2019 demonstrated the degree to which radicalisation had penetrated the local population, where even educated young men could be co-opted by a combination of ideological indoctrination and psychological manipulation. We may have struck back at Balakot, but the adversary’s long-term strategy remained intact: keep India on edge, spread fear, and continue to exploit our political and sectarian divides.

“‘Our agencies do not lack courage or competence. What they lack is a shared battlefield map.”

Delhi, as the capital, has always been their preferred testing ground. A small blast in Delhi carries more symbolic weight than a larger attack elsewhere. And that is why this incident matters. It signals not just the persistence of the threat but the evolution of the adversary. What troubles me the most, though, is the internal dimension.

Delhi, as the capital, has always been their preferred testing ground. A small blast in Delhi carries more symbolic weight than a larger attack elsewhere. And that is why this incident matters. It signals not just the persistence of the threat but the evolution of the adversary. What troubles me the most, though, is the internal dimension.

When a blast occurs in the capital, it means someone slipped through the surveillance net, someone avoided detection despite multiple intelligence organisations operating in overlapping jurisdictions. Over the decades, I have seen how inter-agency rivalry, bureaucratic lethargy, and the lack of a centralised real-time intelligence grid repeatedly create exploitable gaps. Delhi Police may have the strength, the IB may have the informants, the NIA may have the expertise, but unless they act in a single, integrated rhythm, a determined adversary will always find the seam.

We learned this the hard way after the 2008 Mumbai attacks. We studied the incident in detail, and it was evident that multiple warnings had been missed or ignored. The same happened before Pathankot. The same before Pulwama. And if we are honest about it, the same dynamics are likely at play now.

The fact that the adversary has managed to strike again in Delhi indicates both persistence on their part and complacency on ours. But the more worrying shift, in my view, is the changing face of radicalisation. Every generation of soldiers has had to confront a different version of the same threat, but today’s version is subtler and more dangerous. Radicalisation no longer occurs only in mosques, madrasas, or foreign camps. It occurs online, in closed chat groups, in professional networks, and increasingly, among individuals who outwardly appear educated, integrated, and stable.

The fact that the adversary has managed to strike again in Delhi indicates both persistence on their part and complacency on ours. But the more worrying shift, in my view, is the changing face of radicalisation. Every generation of soldiers has had to confront a different version of the same threat, but today’s version is subtler and more dangerous. Radicalisation no longer occurs only in mosques, madrasas, or foreign camps. It occurs online, in closed chat groups, in professional networks, and increasingly, among individuals who outwardly appear educated, integrated, and stable.

“When a doctor is radicalised, he does not pick up a gun, but he can create dozens who might. That is the true danger of ideological infection.”

In recent years, even the security establishment has been surprised by the ideological drift among some Kashmiri professionals, particularly doctors, engineers, and academics. I remember interacting with young Kashmiri medical officers during my service, and they were some of the brightest minds, disciplined, compassionate, and dedicated. Yet the current generation faces a different environment.

Online propaganda, curated victimhood narratives, doctored videos, and sophisticated psychological warfare campaigns emanating from across the border have specifically targeted Kashmiri youth. When you weaponise grievance and identity and then combine it with external facilitation and digital anonymity, you create fertile ground for radicalisation even among society’s most educated layers.

The involvement of Kashmiri doctors in the online dissemination of ideological content is a matter of grave concern. These are individuals with influence, social respect, and access. A radicalised doctor can spread ideology quietly and convincingly within peer networks, far more effectively than a militant on the street. I know the medical fraternity in Kashmir well enough to say that the vast majority remain committed professionals, but even a small minority slipping toward extremism poses long-term challenges.

Counter-radicalisation in Kashmir must now move beyond conventional deradicalisation centres and police outreach. It must penetrate institutions, universities, hospitals, coaching centres, private clinics, and build relationships that go deeper than surveillance.

Radicalisation is a psychological process, and it must be countered psychologically.

The Delhi blast must be seen in this expanded context. Terror modules today can be run by individuals who never set foot in Pakistan, who never meet a handler physically, who never cross a border. Professional radicalisation creates nodes of influence that are invisible to traditional intelligence. And that is why our way ahead must evolve.

The Delhi blast must be seen in this expanded context. Terror modules today can be run by individuals who never set foot in Pakistan, who never meet a handler physically, who never cross a border. Professional radicalisation creates nodes of influence that are invisible to traditional intelligence. And that is why our way ahead must evolve.

For India’s future security, the most important shift must occur in our mindset. We often talk about “intelligence failure,” but the truth is that intelligence in India still functions in compartments. The IB collects. The state police monitor. The central agencies investigate. But the enemy does not operate in so many fragments. They operate as one organism, adapting continually. India must develop an integrated counter-terror architecture that is real-time, centralised, and flexible.

Delhi needs a fusion centre where intelligence from IB, Delhi Police, NIA, RAW, NTRO, and other agencies is not merely pooled but analysed jointly by teams sitting together. Every major country facing persistent terror threats, Israel, the UK, and the US, has adopted this model. We continue to treat it as an aspiration rather than a necessity.

“A small blast in Delhi sends a louder message than a big blast anywhere else. The enemy understands symbolism far better than we give them credit for.”

Second, our HUMINT networks must be rebuilt. Technology can detect patterns, but humans detect intent. In my years in counter-insurgency operations, I learned that there is no substitute for local networks, community engagement, and psychological mapping of vulnerable clusters.

Second, our HUMINT networks must be rebuilt. Technology can detect patterns, but humans detect intent. In my years in counter-insurgency operations, I learned that there is no substitute for local networks, community engagement, and psychological mapping of vulnerable clusters.

Delhi’s migrant belts, dense rental localities, and transient populations must be monitored through live, dynamic human networks that supplement technology, not replace it. Next comes the need for counter-radicalisation. The radicalisation of Kashmiri youth, particularly professionals, requires a more sophisticated approach. Outreach programmes must be designed with psychological insight, not bureaucratic stiffness.

We need to engage influencers from within the community, including respected senior doctors, educators, and civil society voices who can counter extremist messaging with credibility. The state must invest in digital monitoring cells that identify patterns early rather than react after indoctrination is complete.

India’s response to the Delhi blast must begin with clear strategic signalling backed by quiet but firm military readiness. Although this incident does not warrant immediate kinetic retaliation, the message must be unmistakable: India’s threshold for proxy terrorism remains low, and any escalation by Pakistan-backed networks will invite a proportionate and pre-calibrated military response.

India’s response to the Delhi blast must begin with clear strategic signalling backed by quiet but firm military readiness. Although this incident does not warrant immediate kinetic retaliation, the message must be unmistakable: India’s threshold for proxy terrorism remains low, and any escalation by Pakistan-backed networks will invite a proportionate and pre-calibrated military response.

Strengthening counter-infiltration grids along the western front, increasing ISR assets over vulnerable corridors, and raising the alert posture of select formations sends a strategic signal without crossing into open confrontation. At the same time, India must deepen covert intelligence operations aimed at dismantling the handlers and facilitators who guide urban modules.

A terror strike in Delhi is not merely a law-and-order issue; it is an attack on national sovereignty. Quiet, precise pressure on the networks across the border and their intermediaries creates deterrence far more effectively than public sabre-rattling.

Diplomatically, India must seize the narrative early and define the incident for the international community before Pakistan attempts to muddy the waters with denials. The world’s appetite for Pakistan’s duplicity has already thinned after Pulwama, 26/11, and repeated FATF warnings.

India should push for renewed scrutiny of the terror financing chains, highlight the hybrid radicalisation ecosystem that Pakistan’s intelligence services continue to cultivate, and rally partners, especially the US, EU, and Gulf states, to tighten pressure on Islamabad’s military–intelligence establishment. Simultaneously, India must intensify its regional diplomacy with Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka to choke off logistical and recruitment pathways.

A calibrated, confident diplomatic offensive ensures that the Delhi blast does not become another routine incident in global eyes but a part of a long, documented pattern that the world can no longer afford to ignore. Externally, India must continue to maintain pressure on Pakistan, not through routine diplomatic statements but through a long-term strategy of exposing the linkages between their state apparatus and terrorist groups.

After 26/11, the world finally saw what we had been saying for decades. But global attention is fickle. We must ensure that every attack on Indian soil is linked publicly, factually, and strategically to the ecosystem that nurtures it. The more Pakistan is exposed, the harder it becomes for them to operate openly.

The Delhi blast is also a reminder that India’s political class must be more united in moments like this. Terrorism thrives in polarisation. When politicians fight, the enemy celebrates. When political narratives blur the line between national security and electoral convenience, the security grid fractures. As someone who has served through multiple governments, I say this not as an ideological statement but as a strategic truth: the enemy watches our political weaknesses with forensic precision.

In my years on the Line of Control, in Kashmir, in counter-terror operations, and later in strategic planning roles, I have seen personally how terrorism morphs but never disappears. We neutralised top commanders, dismantled modules, sealed infiltration routes, and even after all that, the threat would return, sometimes smaller, sometimes bigger, but always persistent.

The Delhi blast is another reminder of that persistence. It may not be large in scale, but it carries the same strategic intent that lay behind the Parliament Attack, the 2005 Delhi blasts, the 2008 serial blasts, Pathankot, Uri, Pulwama and the most recent one at Pahalgam.

What we must do now is refuse to repeat history. We must stop treating each incident as isolated. We must stop allowing inter-agency hierarchy to override coordination. We must expand counter-radicalisation into every layer of society, including those we once considered immune, professionals, students, and even doctors. And we must remember that a nation’s security does not depend only on soldiers or agencies; it depends on the readiness of the entire system to evolve.

“As a soldier, I learned long ago: victory is not the elimination of the enemy, but the elimination of his opportunity.”

As I reflect on the latest blast, I am reminded of an incident in 2008, when I was commanding a brigade in Shopian, Pulwama and Kulgam. We had just survived a particularly difficult ambush when one of my commanding officers told me, “The enemy is not the man who fires at you. The enemy is the idea that made him pick up that gun.”

That statement has stayed with me for decades. Today, when radicalisation spreads through smartphones more effectively than pamphlets, when terror handlers operate from behind digital masks, and when educated minds fall prey to ideological distortion, that wisdom has never been more relevant.

“If we treat every blast as a lesson, not a headline, we may finally deny the enemy the one thing he counts on: our silence between the attacks.”

Delhi will recover; it always does. But recovery alone is not victory. Our victory will lie in ensuring that such attempts grow rarer, costlier, and ultimately futile. The enemy must realise that India’s patience is not weakness, its restraint is not timidity, and its openness is not vulnerability. For those of us who have served a lifetime guarding this nation, blasts like these are not just moments of sorrow; they are reminders that vigilance is not seasonal. It must be a permanent state of mind. And if we learn from history, not just remember it, we will ensure that the tragedies of the past become the foundations of a stronger, more secure future.

Delhi will recover; it always does. But recovery alone is not victory. Our victory will lie in ensuring that such attempts grow rarer, costlier, and ultimately futile. The enemy must realise that India’s patience is not weakness, its restraint is not timidity, and its openness is not vulnerability. For those of us who have served a lifetime guarding this nation, blasts like these are not just moments of sorrow; they are reminders that vigilance is not seasonal. It must be a permanent state of mind. And if we learn from history, not just remember it, we will ensure that the tragedies of the past become the foundations of a stronger, more secure future.

The author is a former Director-General, Assam Rifles with extensive experience in the Defence and Space sector, holding dual PhDs in Defence, Strategic Studies, and International Relations. He is also a Visiting Fellow at CLAWS and a respected UPSC personality test examiner and mentor.